Speaking of the alignment of people, the Dutch Revolt, which started in 1566, is a prime example of the unpredictable nature of political magnetism. The Spanish Netherlands, which today consists mainly of the Netherlands and Belgium, was controlled by the House of Habsburg and the Holy Roman Emperor in 1566. The independent-minded and disunited subjects of the Spanish Netherlands spoke different languages (e.g., Dutch, Spanish, German, French, Latin, and Luxembourgish.) They had different religions, cultural traditions, economic interests, and political alliances. They were a collection of disunited, independent city-states surrounded by manorial estates and lots of lowland water. If they were a collection of magnets, any metal filings would shift toward one pole and soon to another. However, they had one problem.

Like other geographical chokepoints in history, the Spanish Netherlands was a vital cultural, economic, and geographical region with active relationships with England, France, Germany, Scotland, Spain, and others. Over the last 500 years, most of the major European wars were fought in what was once called the Spanish Netherlands. We have all heard of Flanders Fields (especially the World War I poem “In Flanders Fields” by John McCrae) and the Battle of the Bulge in World War II. Of particular importance in the context of both the 1500s and the Spanish Netherlands was the Protestant Reformation. Although Martin Luther’s 95 Theses were said to light the fires of the Reformation, there were many causes and precursors to the larger European revolt against the all-powerful Catholic Church, whether the church was in Rome or Avignon.

The embers of the Protestant Reformation not only lit the fires for change across Europe but also increased the intensity of the distrust of the occupied towards their Spanish masters in the Spanish Netherlands. A functional separation between church and state did not exist in 1566, so religious matters crept into politics and often trumped politics. The evolving and complicated provinces of the Spanish Netherlands slowly found Spanish religious despotism intolerable. The founding of the Dutch Republic is at the nexus of the old world and the emerging modern world.

William of Orange

The William of Orange (also known as William the Taciturn, William the Silent, and William of Nassau-Breda) is readily confused with his more famous great-grandson, William III, King of England, Scotland, and Ireland and also known as William of Orange. Many Williams of Orange have existed throughout history, including a famous pigeon used by British intelligence during World War II. William the Pigeon flew about 250 miles from Arnhem to England in about four hours to deliver a message that was said to have saved over 2,000 soldiers at the Battle of Arnhem (aka, A Bridge Too Far) in 1944.

The William of this discussion was born in 1533 in Dillenburg (now part of Germany), whose father was the German Count of Nassau and was called William the Rich by history. While a young man in Dillenburg, William’s cousin died. With his death, young William became the Prince of Orange. He inherited two large estates in what is now the Netherlands and a property in the Principality of Orange in Southern France (la Principauté d’Orange.) After becoming the young Prince of Orange, he was sent to the households of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V in Breda and Brussels to be royally educated and raised as a dutiful Catholic.

William’s experimentation with political magnetism began when he spent time at his inherited estates in the Spanish Netherlands. Given his inherited wealth and honorable service to the emperor, he became one of the most important noblemen living in the Netherlands. When William’s Emperor, Charles V, died and was replaced with the inquisition-minded Phillip II of Spain, William was slowly repelled and disgusted by the viciousness of Phillip II’s attacks on the Protestants in the Spanish Netherlands. For a few years, William kept silent and remained an overt Catholic, despite the increasingly despotic rule of King Phillip. King Phillip was adamant that everyone in the Spanish Netherlands should be compulsively and magnetically aligned with his version of Catholicism. He was prepared to kill or drive out every heretic in the land, just as the Spanish had driven, killed, or converted all the Jews and Muslims in Spain. Gradually, the Prince of Orange’s pole of loyalty began to swing away from the Holy Roman Empire, the Spanish occupiers, and the Catholic Church toward the pole of a slowly emerging multi-cultural, multi-lingual, and multi-religious Dutch population.

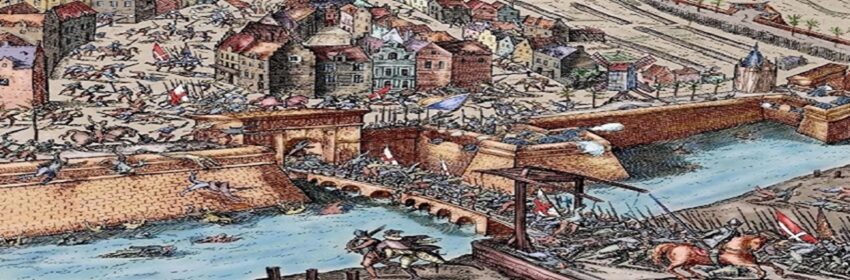

The Spanish Netherlands (the “Low Countries”) became a seething bed of resentment against Spanish rule. Consequently, 74 years before the English Revolution, 210 years before the American Revolution, and 223 years before the French Revolution, the Eighty Years’ War (the Dutch Revolt) began. Since the various regions within the Spanish Netherlands were a disunited collection of provinces, they did not initially view themselves as a nation or a collection of provinces with a common purpose. The only force for unification came from the external, heavy hand of the Habsburgs, Phillip II, and the Catholic Church. A parliament-like entity called the States-General was forced upon them to better manage the Spanish Netherlands in 1549.

Within each province, one or more members of the nobility believed they had rights given to them by previous Burgundian royalty. Phillip II sought to cancel the past Burgundian contracts and force the nobility to swear a personal oath of alliance to him. [Does this sound familiar? All insecure tyrants think alike.] The sycophants swore the oath, but a few, including William of Orange, declined.

While many of the high nobility figuratively kissed King Phillip’s ring, most lesser nobles, particularly the Protestants, took umbrage with the king’s religious authoritarianism. King Phillip and his representatives scoffed at their feeble attempts and called them “beggars.” Wisely, these rebellious lesser nobles initially proceeded cautiously by proposing moderation and compromise.

Over time, they were angered and emboldened by the Catholic King’s increasingly forceable subjugation. Concurrently the more radical Protestant ministers rallied their religious flock, and the word got out that Catholic Churches should be attacked if the Catholic subjugation continued. Over time the disparaging term “beggars’ became a badge of honor for the rebels from the Low Countries.

The Dutch Revolt

Although some Dutch nobles were still loyal to the Spanish King, the King had two choices: capitulate to the rebels’ demands or crush the rebellion. In 1566 King Phillip II chose the latter. He raised an army to subjugate the rebellious provinces militarily. The Protestants then began to destroy Catholic images and property as the conflict expanded. Destroying Catholic icons and objects made King Phillip livid. Over 1,000 “heretics” were summarily executed by the Spanish King, including two high regional nobles. William of Orange retreated to his ancestral home in Germany to begin the resistance against the vengeful Spanish King. William and his brother, Count Louis, organized a rag-tag group of seafaring privateers called the ”Sea Beggars” to harass the Spanish at sea. The sea blockade forced the Spanish King to resupply his attack on the Low Countries via a long, slow land route.

I will not provide all the details of the Dutch Revolt. It was an extended period of conflict with lots of Dutch defeats. I will summarize rather than give a detailed description of the Revolt. I am puzzled why so little is known about the Dutch Revolt in the USA, but ignorance seems to be bliss. Why should Americans know about Dutch history when they know so little about their own?

The many books I read about this period seem to concur that the William of Orange was a remarkable leader. He inherited great wealth and was raised as a royal who defended the Catholic Church. He could have been an ideal noble who kissed the ring of whoever was his sovereign at the moment. However, because of the brutality and intransigence of Spanish King Phillip, he unintentionally became embroiled in a major clash of cultures. He found himself as a moderate between extremists on opposite poles.

Just as George Washington is regarded as the father of the United States, William is regarded by the Dutch as the father of the Netherlands. Likewise, George Washington fought on the British side against the French in the Seven Years’ War, and William of Orange was a soldier and diplomat in the service of the Habsburg Empire. However, they both switched their magnetic poles in the face of uncaring and unrelenting fanatical autocracy. It is essential to highlight that neither George nor William was an extremist. They were practical men who switched sides due to their empathy for the pain of their people and the tyranny of their oppressors. Their primary motivations were to construct and repair the institutions of their respective evolving societies. They were institutional builders, not fanatical destroyers.

Like George Washington, William of Orange and his allies suffered many defeats at the beginning of the revolt. William led a formidable opposition to the Spanish but was unfortunately assassinated by a Portuguese bounty hunter (in the service of Spain) in 1584. He was the first prominent political figure in world history to be assassinated by a gun. Unfortunately for the assassin, his primitive gun exploded, and he lost his hand. However, his pain was short-lived since William’s bodyguards immediately dispatched him.

The assassination and continuing barbarity of the Spanish caused Queen Elizabeth and Protestant England to finally align with the Dutch resistance, which tilted the balance against the Spanish. I will not go into any detail but suffice it to say that one of the outcomes of the larger international conflict was the Spanish Armada’s historic defeat in 1588. The conflict dragged on, but in 1648, the war between Spain and the United Provinces ended. The United Provinces had finally forced a despotic ruler out of their lands.

William the Silent is a relatively unknown leader who profoundly impacted the modern world. Instead of following the autocratic patterns of the past, he broke with Habsburg tradition by getting out of his noble carriage and talking to the people of the Low Countries. He discussed the problems of other nobles, merchants, religious leaders, sailors, soldiers, etc. He was a transitional leader with one foot in the old autocratic world of a monarchy and the other in the modern democratic world.

The final paragraph of “William the Silent, William of Orange 1533-1584” by C. V. Wedgwood, Copyright 2021, sums up his contribution to the development of democracy in a heterogeneous environment and the lessons for overcoming tyranny.

“There have been politicians more successful, or more subtle; there have been none more tenacious or more tolerant. The wisest, gentlest and bravest man who ever led a nation, he is one of that small band of statesmen who service to humanity is greater than their service to their time or their people. In spite of the differences of speech or political theory, the conventions and complexities which make one age incomprehensible to another, some men have a quality of greatness which gives their lives universal significance. Such men, in whatever walk of life, in whatever chapter of fame, mystic or saint, scientist or doctor, poet or philosopher, and even – but now rarely – soldier or statesman, exist to shame the cynic, and to renew the faith of humanity itself.”

Footnote: My interest in the Dutch Revolt was initially triggered by the fact that my paternal 7th great-grandfather had enough of the war with Spain and left the Spanish Netherlands in 1640 for the promised land of New Amsterdam (now New York City.)